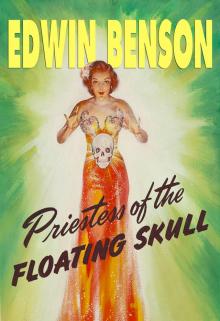

- Home

- Edwin Benson

Priestess of the Floating Skull Page 3

Priestess of the Floating Skull Read online

Page 3

A waiting car took them through Moscow’s streets to a small building which seemed to be a combination house and shop. The shop was converted into a laboratory that was a queer mixture of radio and chemical laboratory Vorosh noted as they passed through it and into the house itself. Inside, he discovered a comfortable living room.

“Sit down, please,” said Vanja, removing her coat, and putting her uncanny burden down on a table. Its glaring empty eyesockets seemed to stare at Vorosh as he seated himself.

John Zymanski fetched glasses and Vanja poured a drink.

“Now,” said Vorosh desperately, “What’s all this about?”

Vanja put her glass down.

“Perhaps I had better begin at the beginning, so that you will understand the whole complex structure of things,” she said. “And to do that, I must go back to the time before the war—”

SHE leaned back, hands resting on the chair arms, head back, eyes staring upward reflectively.

“It was in Warsaw. I was on the stage with a mind-reading act. John, here, came to the theater often to see me. We have been friends for a very long time. I was Russian, but my folks had been killed in 1919 when the White armies and the Germans besieged Tsaritsin . . .”

She looked at Vorosh a moment. “You should know of that incident in Russian history. Your name is the same as that of the savior of Tsaritsin, or Stalingrad, as it is called today. Can it be possible that you are related.” Vorosh shook his head.

“No. That Voroshilov was no relation, although I wish he were!”

“Well, just before the Nazis attacked Poland, in 1939, John had been working on a new type short-wave radio transmitter. After many months of hard work, experimentation, he was confronted with failure—his radio did not work . . .”

John Zymanski spoke up.

“That was a blow! I remember how I came to you for solace, Vanja. We went to a little restaurant after the performance, and I told you of my work, and what had happened to it.”

“Yes,” Vanja reflected. “I suggested that I would like to see your laboratory, and we went there. In a short while we were trying the new radio again, and then a fantastic thing occurred; because I heard a voice. It was a voice, speaking a name. A name that I did not recognize . . . then!”

“Who?” asked Vorosh.

“The name was Rudolph Hess.”

“Hess! He’s Hitler’s right hand man! Number three Nazi!”

“Yes. And I heard his voice, sometimes clearly, sometimes too faint to understand, and it seemed to me that he was referring to an invasion of some European country by Germany. Of course, at the time, I thought the idea preposterous. Hardly anyone expected war so soon. At least, not all-out war.

“It seemed to me that the voice was coming from the radio, but John could hear nothing . . .”

“I have never heard anything from that radio!” said John Zymanski. “But I know that it does work, because many others have heard it—without realizing that they have heard it.”

“NOW wait a minute,” protested Vorosh. “Do you mean to tell me that this radio is what I heard three thousand miles away?”

“No,” said Zymanski. “Actually, no one, not even Vanja, had heard anything from this instrument. It does not either pick up or broadcast sound. It broadcasts and receives incredibly short waves; so short that they are in the wave-bands of the electric vibrations employed by the human brain in the process of thinking.[1] By some strange chance, the coils of this radio are exactly attuned to the waves from Vanja’s mind, so that she can receive them even at a distance. Thus, the thoughts of anyone with the same vibrations as Vanja, come over the radio, are amplified, and are received by her.”

“Then Rudolph Hess’ mind is open to Vanja?”

“Exactly. And Vanja’s mind is open to Hess—although he does not know it.”

Vorosh shook his head.

“I don’t exactly understand, especially where this can be of any great use—I can see where you could spy on Hess, and learn secrets even though he has fled to England, but . . .”

Vanja broke in again.

“Let me go on with my story, and then perhaps you will understand better. As I was saying, I heard Rudolph Hess, apparently speaking to me through that radio. At first, I actually believed it was his voice. Now I know he was just thinking, thinking deeply, and reviewing future plans of the Nazis. It seems that only deep concentration strengthens thought waves enough to enable this radio to pick them up.

“Later we found out that perhaps one out of every fifty persons are on or near the wavelength peculiar to the radio. But most of the signals are so distorted that reception is not very good. Only two persons in the whole world, so far, have perfect contact . . .”

Vorosh looked at her.

“Am I to understand that I am one of those two persons?”

“You are the more perfect of the two,” Vanja admitted. “Even over three thousand miles of space, I was able to hear your thoughts, and was able to impress mine upon you. That was one reason why I simply had to reach you, learn who you were.”

“So that’s why you kept asking my name?”

“Yes. You see, it happened that I was trying to contact the mind of Rudolph Hess, when suddenly I heard a new voice—yours—cursing the Nazis, and I heard very strongly, some comments on Moscow and on the Red army. To say that I was startled would certainly be understatement of the weakest nature. Then, while I listened, and while you went through the process of taking your plane aloft, I heard the most amazing story I have ever heard in all my life I understood perfectly, as though I was with you in that plane, what was happening. And I realized, as you did, your danger, and the possibility of your death. That was one thing I desired least of all. Here I had a perfect contact, and obviously one emphatically loyal to and interested in our cause, and you faced terrible danger.

“I KNEW you were freezing to death, so I employed something that I had long wished to test, and which John and I had been working on to perfect—a method of hypnosis by means of this radio, to be used on Rudolph Hess to carry out certain plans we had, and still have, in mind.”

Vorosh gasped.

“You mean you hypnotized me?”

“That’s it. When you saw the skull floating above you, it was impressed upon your mind by mine. That is one of the reasons the radio is now encased in its present gruesome camouflage—the other you will learn of as I continue my story—because It forms the attention point upon which hypnosis is based.[2] Forming a mental image of the skull by looking at it directly, I can make the person who receives my thoughts also see the skull apparently floating before him, or anywhere his own mind chooses or happens to picture it.

“The average person is very superstitious regarding the human skull, and the sight of one certainly attracts concentrated attention. Thus, John and I reasoned, we could hypnotize a person in tune with my mind against his will, because he would be unaware of any attempt to usurp it. Thus, thoughts impressed on him might be interpreted by him as his own, or, as a voice out of nowhere, my voice. I find that I can do both with equal facility.”

“So that’s what you did when you questioned me before General Vidkov?”

“Yes. And that’s why I never let you answer a question. You see, I got your answer from your mind before you could speak. Also, I got correct answers even in cases where you might have answered differently. Had you been lying about being born in Moscow, my innocent statement that I already knew where you were born would have been mentally contradicted by your mind as a matter of fact.”

“Clever!” exclaimed Vorosh.

“Then, when I put that thought in your mind that you denied as your own, it was to test your real feelings toward the Nazis. I certainly got an answer!” Vanja rubbed her arm ruefully. Vorosh was staring at her.

“Then,” he said slowly, “when you hypnotized me in that plane, and put me to sleep, you were trying to . . .”

“Trying to save your life,” she finished. “A s

ubject under hypnosis can undergo and survive things that would normally be impossible for him to stand. Thus, when I found you were in danger of death from freezing, I tried to avert it by hypnosis. I felt that whatever amazing storm was bearing you aloft must inevitably abate and let you fall. That’s why I had you turn off your motor—to make sure that you would have gas to fly out of trouble when the storm was over.”

“Then I do owe you my life?”

“Perhaps,” she said. “But I owe the Fates much more. I could not have known that you were to be carried by that freak stratosphere storm to my very door. My only purpose was to save your life, so that I could contact you later and discover whether you could be of use to our cause.”

SHE was silent a moment, and Vorosh let his eyes take in the skull again. “You were speaking of another reason to encase the radio in the skull—” he reminded her.

“Yes. I got the idea of using the radio in my mind-reading act. We had to conceal the radio, so John built it into the skull. In my act, I can apparently cause it to float in front of me by means of tiny invisible wires. This focuses the attention of the entire audience, and I can receive and impress thoughts from and upon persons in the audience who are within range of the wave band. Usually there are three or four in the house whose thoughts I can thus read.

“My act, thereafter, became sensationally successful. I was on my way to an international reputation, and was booked to appear in Berlin. But before we could accomplish this, the blow fell—Poland was invaded!”

John leaped to his feet, his face white with recollection.

“The foul, murdering dogs!” he cried. “Overnight Warsaw became a hell of death and destruction. Women and children, torn apart as though by a pack of hungry wolves. They shall pay for that! Oh, how they shall pay!”

“John!” said Vanja compellingly.

Zymanski sat down again, trembling with the reaction.

“I’m sorry, Vanja. But every time I picture it, a red wave sweeps over me.”

“You are not the only one,” said Vorosh grimly.

Vanja went on with her story.

“It was then that we decided that we would use the contact with Rudolph Hess in whatever way we could. We realized then, for the first time, what the possibilities were. We knew then what had been the significance of what I had heard.

“But the obstacle remained—we were at too great a distance from Hess. We could only rarely get his thoughts, and then many times we missed the important information. And, then, too we found we could not depend on some of the things we learned, because exactly the opposite happened. It is one of the things I do not understand yet . . .”

Vanja’s voice trailed off a moment, then she resumed.

“For a time we remained in Warsaw, even after the Germans entered the city. I managed to resume my performance, for the benefit of German soldiers, and partially so we could complete and test what we were planning to do. It was our plan to bring my act to the attention of high Nazi officials, and eventually, even in spite of the war, be brought to Berlin.

SEVERAL things we learned from contacts with the audience. Secret messages, plans, and vital information, which we smuggled to the underground, and to Russia. We learned of the invasion of the Low Countries too late to warn anyone of it, even if we could have contacted the British and French. For some reason, even Hess seemed to be unaware of the exact time-table of the Nazi invasion.

“Once we were instrumental in destroying a whole train-load of ammunition; another time we learned of the visit of a high official, and laid an ambush for him. He died.

“Then I learned of the invasion of Russia! There was only one thing to do, and we did it. We managed to fly, by night, to Russian-occupied Poland, and even though John hated us bitterly . . .”

“Not you,” interrupted the Pole. “Only I didn’t understand at that time why Russia should leap upon a beaten nation and grasp part of the spoils. Now I know it was because Stalin knew that one day he would be fighting the Nazis, and he needed a territorial buffer to give him time to prepare and to enable him to slow the drive that was coming. You explained that to me that night, Vanja, even while we fled, to where I did not know at the moment.”

“You were difficult,” said Vanja, smiling. “I feared for a time that you would desert me, and I needed you so badly. You see: now it was a personal matter to me. My own country was threatened with the horror that had befallen yours. I had to try to warn them. As it turned out, we were too late to do much good. But one thing we did accomplish, we placed in Hitler’s way several divisions of troops who managed to slow that first onslaught down. If that had not been done, perhaps today the enemy would be inside Moscow, instead of battering at its defenses . . .”

Vanja stopped speaking and listened. Vorosh heard the dull rumble of distant gunfire which had been in his ears all day.

“We’ll hold them,” she whispered. “We must hold them!”

“What is your plan, and where do I fit into it?” asked Vorosh.

Vanja looked at him.

“Perhaps you will not want to fit into it. It may mean death.”

Vorosh looked at her steadily.

“Turn on your radio, and you will get the answer to that,” he said.

“Somehow,” she said softly, “I think I would have known your answer even without a radio. . .”

“WELL, our eventual plan is to get to Berlin. But to do that, we must first return to Warsaw. We actually left Warsaw, enroute to Russia, before the invasion began. We did it with permission, because after all, I am Russian, and John, though Polish, was my assistant, and was securing passage only into another part of Poland, held by a country not at war with Germany. So, we can ‘escape’ from Russia with quite a bit of logic. It is not too unnatural for a talented showgirl to want to further her career in a place more suited to her talents, the German Reich.”

Vorosh grinned admiringly.

“Logical? It’s perfect—even to the egotism of the ‘supermen’ !”

She smiled.

“I have one more logical point to make, which is where you come in, in part. Our escape to Warsaw is to be made in your American P-40. You were ‘caught’ in Russia when the war broke out, with a P-40, an American ship, which America, blood-sucking business monger that she is, wished to sell in quantities to the Russians. (The Germans will be eager to believe that.) So, threatened with the theft of your ship’s design, you also escaped, by flying the ship into German-held territory. And in so doing, you flew us in the same direction.”

Vorosh frowned.

“I’m afraid your point is too well put,” he said. “I certainly don’t propose to have the Nazis stealing those same designs!”

“Certainly not. The Nazis could hardly copy the design of a plane that has crashed and burned . . .”

“You mean?”

“That you will set the ship afire, bail out over German territory, and let it crash. You can say the motor caught fire.”

“I see,” said Vorosh. “But your plan has one fault . . .”

“And that?”

“The P-40 will not carry three passengers!”

“It need not,” said Vanja.

“Need not?”

“No. You see, that is where the other part of your contribution to the cause comes in. You are going to be my new assistant. John will remain here. And the fact that I am unscrupulous enough to desert my former partner, simply to escape with you, will help build the illusion with the Nazis that no suspicion need fall on my motives.”

“One thing more,” said Vorosh. “How far is it to Warsaw from Moscow?”

“About eight hundred miles.”

Vorosh settled back in his chair.

“Then there is nothing to halt us,” he said. “The range of the P-40 is somewhere between eight-hundred and a thousand miles.”

CHAPTER IV

“Flight” Into Intrigue

THE P-40 roared through the night, flying high and fast. Down below

was a blanket of clouds that hid the earth. Up here, the moon was bright. The clouds looked like a sea of silver enveloping the earth.

The two figures in the tiny cockpit were crowded and uncomfortable. The P-40 had never been intended to carry two persons.

“We ought to be very close now,” said Pete Vorosh. He spoke directly into Vanja’s ear, pressed against his shoulders, both through necessity and because it was cold in the tiny ship.

She looked at the gasoline indicator, and at the mileage meter. The gasoline gauge was almost down to zero. The speedometer had already ticked off 780 miles.

“Very close,” she said. “I think we had better go down now, through the clouds. Perhaps I can see . . .”

“I doubt it. It’ll be black as ink down there, and Warsaw won’t have a light in it. It’ll be blacked out completely by the Nazis.”

“Tonight there will be an accident—a house will burn down, perhaps because a stove proved defective . . .”

“Oh. I see. Your plans have been well-laid.”

Vanja shrugged.

“We can only hope.”

Vorosh dipped the nose of the plane down, and in a long glide, lost altitude slowly. They entered the clouds and the moonlight faded swiftly. All became utterly black. Vorosh switched off all the lights in the cockpit except the altimeter, and kept his eyes glued on that.

“See anything yet?”

“Nothing.”

Vorosh grunted.

“We’re below the clouds now. Altitude about four hundred feet.”

“There are no lights,” said Vanja. “I’m afraid we’ll have to do without anything to guide us.”

“We can go a little further,” said Vorosh. “I don’t believe we’ve reached the city as yet.”

He turned off the altimeter light, and they flew on in pitch darkness for five minutes longer. There was no glimmer to break the darkness below. At last Vanja stirred.

“This is it, Peter,” she said. “No use waiting. I’ll jump, then you get ready, set the ship on fire as we planned, and follow me. The light from the burning ship may help us to see where we will land. And it will attract attention and help us to be picked up.” Vorosh gripped her hand suddenly.

Priestess of the Floating Skull

Priestess of the Floating Skull